Square’s Margins, Square vs. Shopify

Square, now called Block, reported Q2 earnings last week. The company delivered solid growth, with net revenues excluding bitcoin and AfterPay of $2.41 billion, up 23 percent YoY.

Block reports in two segments. The Square Ecosystem includes the Seller business (mostly, the merchant POS, loans and other banking products, and software subscriptions). Excluding AfterPay, Square grew revenue and gross profits 24 percent and 16 percent YoY respectively.

The other segment, Cash App Ecosystem, reported revenue of $732m (excluding bitcoin and AfterPay), up 21 percent YoY. Gross profits on the same basis were up 15 percent YoY.

All in all, it was a decent quarter for Block. There is much to be said about the integration among all the various pieces of Block, and its contrast with Shopify, which has made the opposite choice.

AfterPay

AfterPay is the Australian buy now, pay later (BNPL) operation that Block closed on earlier this year.

The integration of AfterPay into Square will allow merchants to offer BNPL seamlessly to their customers, while Cash App’s Discovery function will allow consumers to find merchants who offer BNPL.

This discovery function is something that AfterPay’s competitor Affirm does inside its app. These network effects of discovery and customer engagement reinforce the Affirm ecosystem. Since Shopify has chosen to outsource BNPL to Affirm exclusively, these benefits accrue to Affirm, not Shopify. On the other hand, Block’s vertical integration with AfterPay increases the value of both the Seller and Cash App ecosystems.

Block’s co-founder Jack Dorsey laid out the benefits of AfterPay’s integration for Square and Cash App on the opening of the earnings call:

The connections we are building, like with AfterPay, are what set us apart and make us so valuable to our customers. In Cash App, we're just starting to bring AfterPay’s discovery capabilities into our ecosystem. The greatest combined opportunity we see is in commerce. AfterPay will introduce discovery and shopping to build on the elements that Cash App has already created around commerce, like Cash App Pay and Boost.

We believe our new design with Cash App will let us scale new products and drive deeper engagement. We're rolling out a new Discover Tab to the main navigation, making it easier for customers to find and use brands and products that can save on with Boost and paying with installments with Afterpay. This lays the foundation for a new experience and enables customers to connect with one another, find offers and search.

And this is just the beginning. We've seen early results but we believe that over time, Cash App will become one of the best ways to discover products, brands and businesses. Also within Cash App, in the second quarter, we introduced a new investing feature, Round Ups, as part of our work to make investing relatable and accessible for everyone. Customers can now round up their Cash App card purchases and invest the fair change in stock or Bitcoin. Round Ups engage customers on other products within our ecosystem, creating more reasons for customers to bring money into Cash App's ecosystem.

Within our Square ecosystem, in May, we announced the in-person integration of AfterPay for Square sellers in the U.S. and Australia, adding to the online capabilities we announced earlier this year with more products to come. With the addition of in-person, AfterPay is the omnichannel tool in our ecosystem which many of our sellers haven't typically had access to, helping sellers grow their sales both online and in person.

Block Compared to Shopify

As I explained last week, Shopify chose not to monetize its merchants by vertically integrating and building solutions for them inside Shopify. As a result, most of the value captured in the Shopify ecosystem accrues to its partner ecosystem and others, including Amazon.

Block, on the other hand, has chosen to build much more functionality internally and to acquire the pieces it didn’t have.

Both companies today have similar sizes in terms of enterprise value. Block’s EV is $48 billion and Shopify’s EV is $41 billion (for reference, Block’s share price is $81 and Shopify’s is $37).

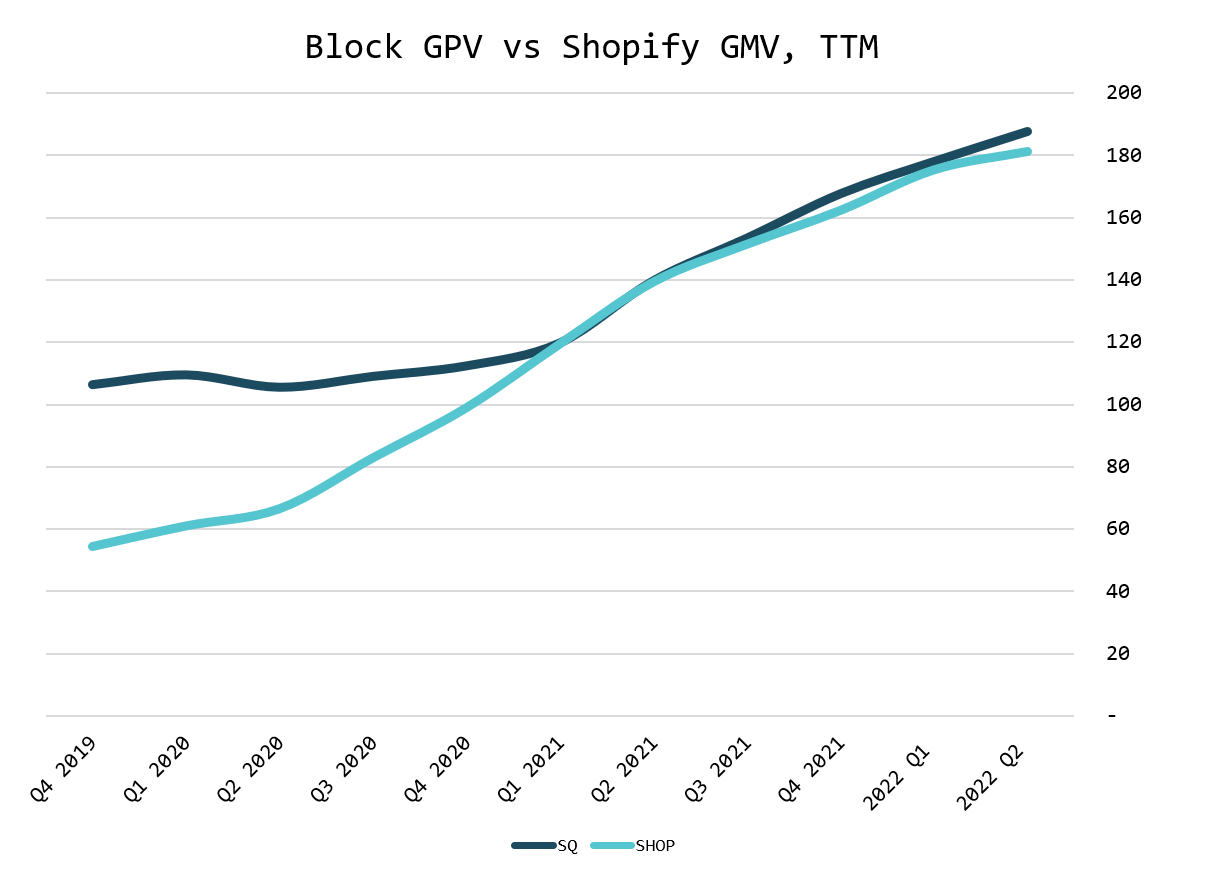

They are also similar in terms of the volume of “money” that flows through them. Shopify’s measure is GMV or gross merchandise volume. For Block, we can look at GPV instead, or the money that flows through its merchants’ points of sale (a smaller percentage of GPV, about 8 percent, comes from P2P payments in Cash App sent from a credit card).

For the last twelve months, Shopify’s GMV was $181 billion and Block’s GPV was $188 billion:

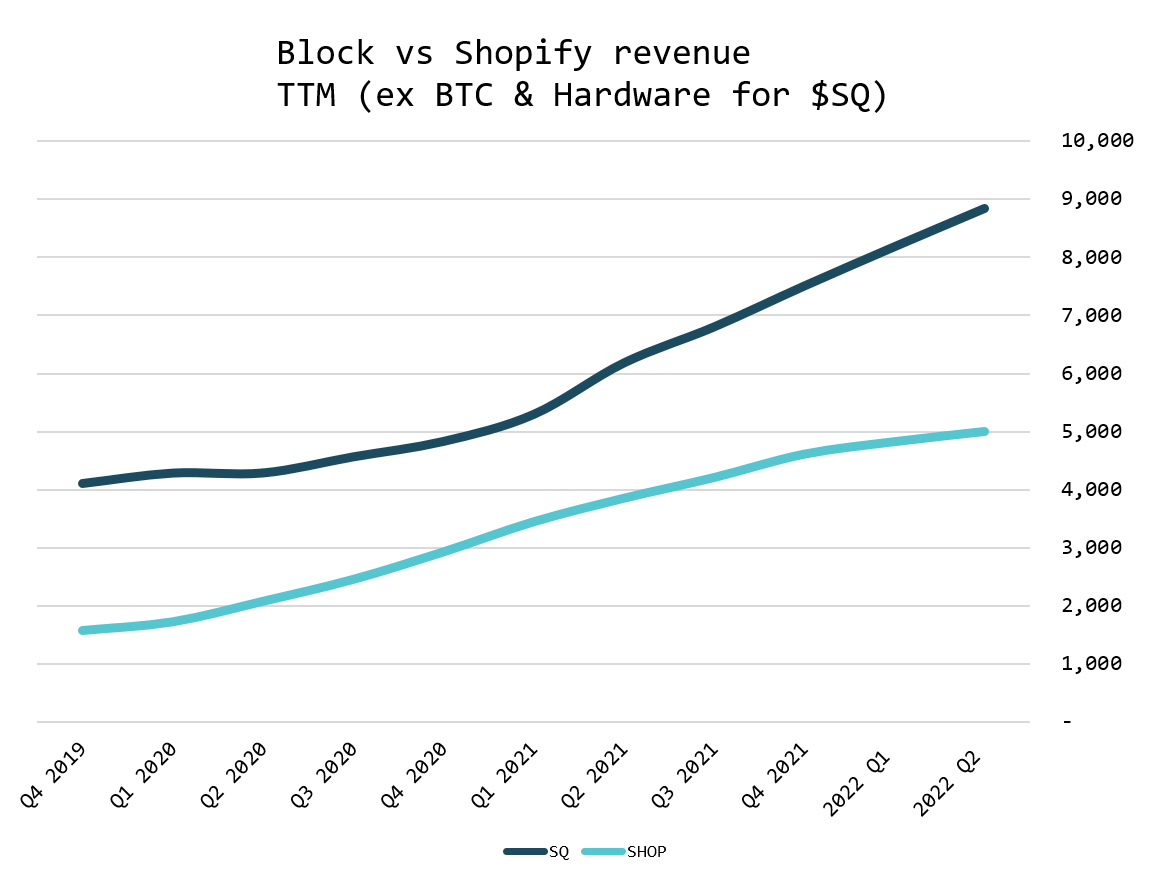

Out of this “flow,” Block has the upper hand in capturing revenues:

Note that Block’s revenues here exclude bitcoin and hardware revenues. Bitcoin is low margin and used solely as an engagement tool within Cash App. Hardware revenues are small and are negative gross margin, as they’re used as a merchant acquisition tool (give away the hardware, make money on the payment flows and software).

Note from the chart that Shopify’s revenue growth decelerated recently to 16 percent quarterly growth compared with 23 percent growth for Block. Block is both bigger by revenues and growing faster.

Block enjoys not only the revenue stream from merchants’ payments and software, like Shopify, but also the digital wallet (Cash App) business.

The benefits are undeniable. Dorsey explained the idea of “diversity of utility” and how when one business “may ebb, the other will flow”:

I think one of the important things that we want to continue to focus on and you all have brought up in the past is we want to make sure that we have diversity of utility. So we believe it's really important that people may come in for a particular reason, such as what we saw during the [seamless] or just a peer-to-peer functionality that we've always provided.

But in terms of retention and also new customer acquisition, it really has to do with like how much utility we're offering, that we're not just focused on one thing such as peer-to-peer transactions or investing or Bitcoin or lending, but it is a place, one place you can do all those things. And we see peers in other industries and other spaces and other countries that have done that very well, which is sometimes referenced as super apps or neobanks.

And we believe that over the long term, that is the right strategy, and that is both for the Cash App ecosystem and also the Square ecosystem. And more importantly, the fact that we have both of those in one company, we believe, is our superpower. So over the long term, we will continue to see a bunch of ebbs and flows within the markets and macro environments. But our strength relies on the fact that we're not just dependent upon one particular use case, one particular utility, but that we offer all of them.

And while one may ebb, the other will flow. And we will continue to build this ecosystem where someone is coming back to the Cash App every single day for something that is of extreme importance in their life, which, obviously, we believe the relationship with money and people's financial empowerment into the economy is critical and we hope to serve them in multiple ways. And we think that is a relationship, that is the strength and that is the resilience. Ultimately, over time, that creates both new customer acquisition but also retention over time.

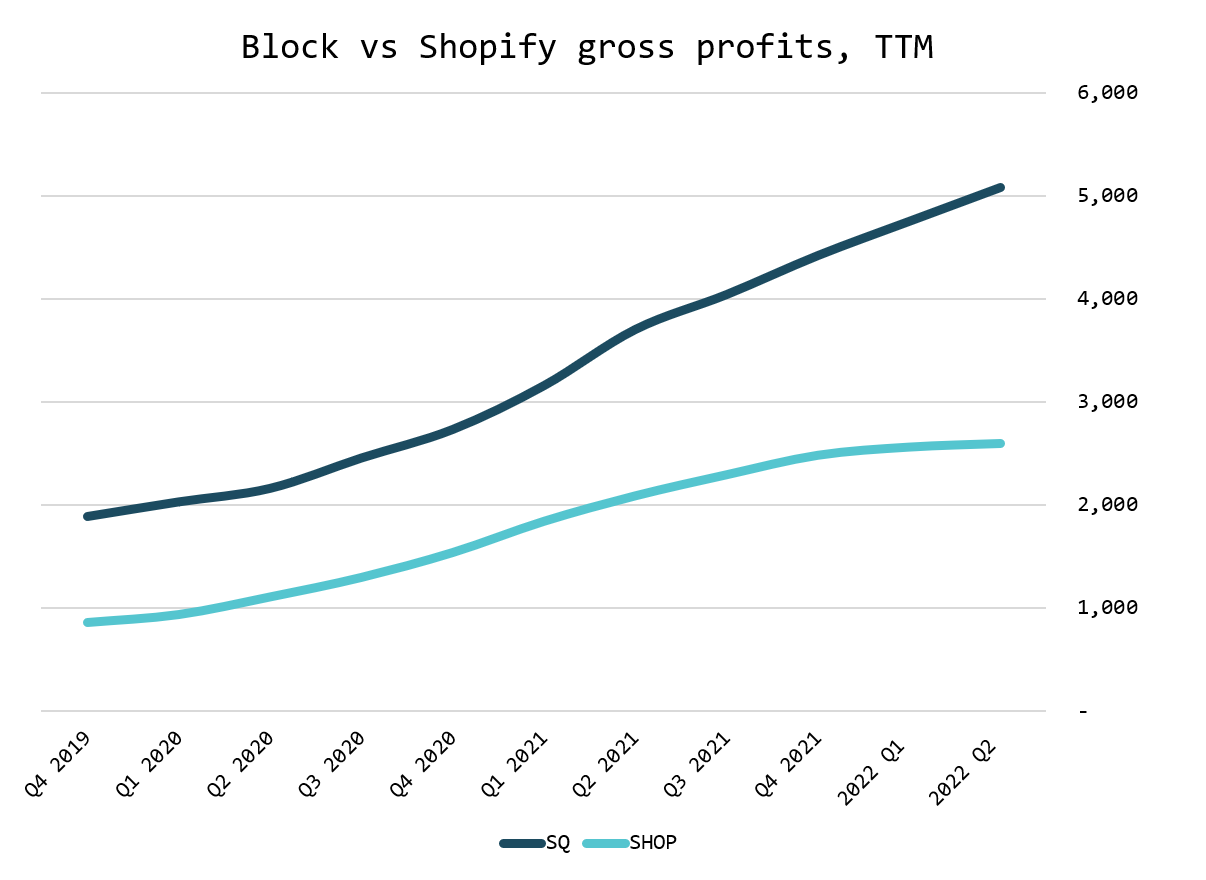

This extra revenue and utility has resulted in more gross profits for Block compared to Shopify:

What About Net Profits?

Gross profits are all well and good, and they are obviously a pre-requisite for heavy investment in product development, engineering talent and customer acquisition. But eventually shareholders must also be paid with GAAP profits (or better yet, a growing stream of free cash flows per share).

This has so far been Block’s big problem.

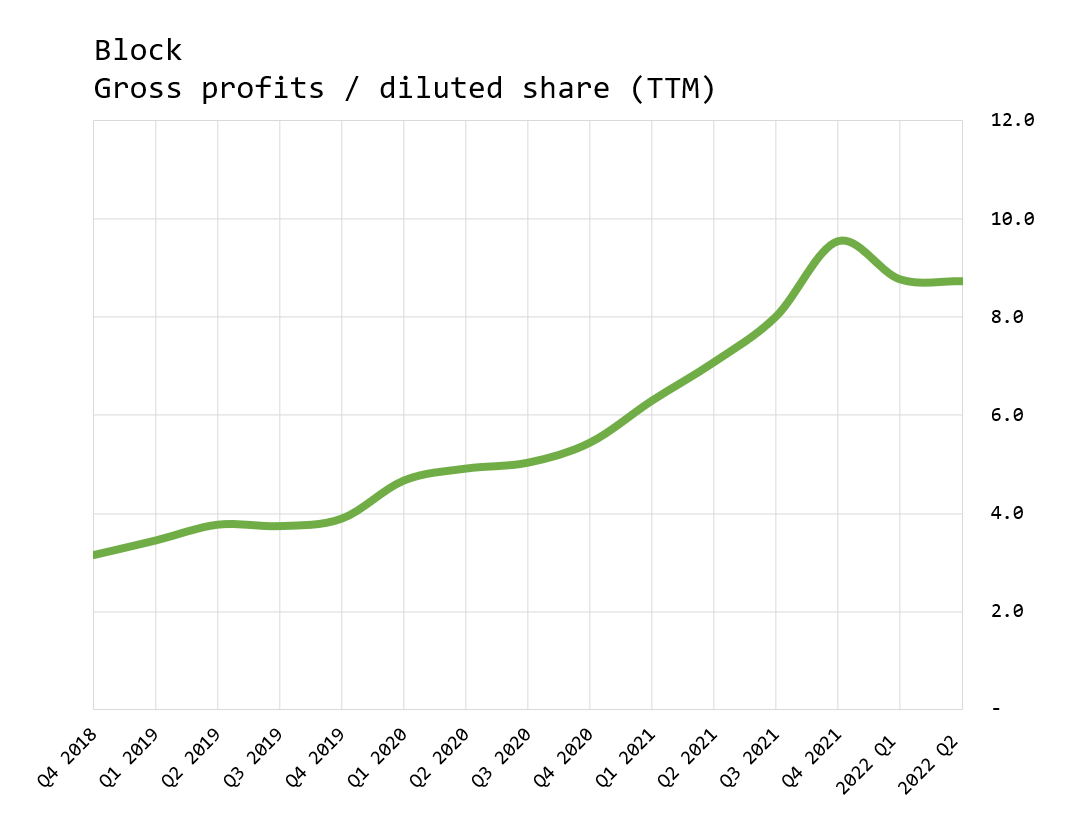

True, Block has increased gross profits per share, despite a massive 32 percent increase in the share count over the last two years:

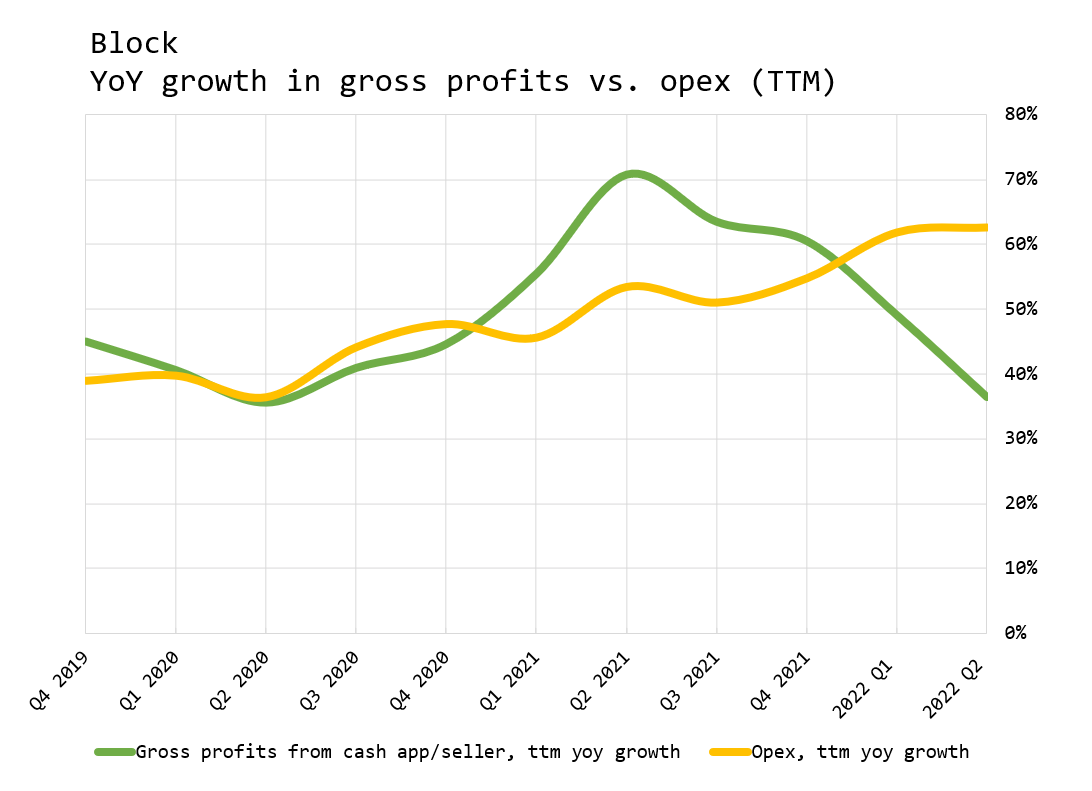

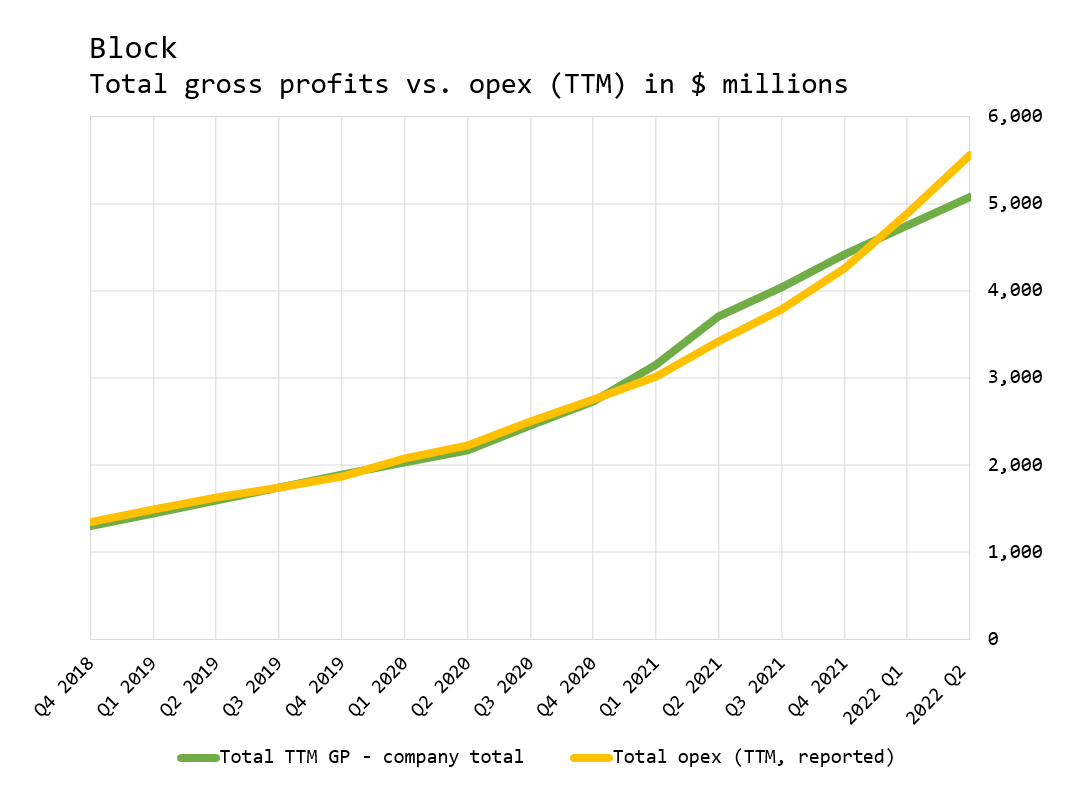

But operating expenses have grown at an even faster pace. In recent quarters, operating expenses have grown faster than growth in gross profits:

As a result, the company has demonstrated no operating leverage at all. If you thought payment companies were among the most profitable businesses around, you’d be right. Visa has operating margins in the mid-60s; so does Adyen. PayPal’s are around 20 percent and going higher (PayPal generates so much free cash flow, it’s buying $4 billion of its own stock this year).

Meanwhile at Block, growth in gross profits has been accompanied by a steady increase in operating expenses, leaving the company with a negative operating margin:

CFO Amrita Ahuja pointed to a reduction of operating expenses of $450m since the start of the year, but obviously this isn’t enough. During the company’s recent Investor Day, Ahuja gave investors a breakdown of fixed and variable expenses for Square and Cash App (slides 56 and 57) but the bottom line is what matters, and Block isn’t delivering.

It's true that Block has terrific unit economics given its low CAC and rapid payback period. However, the company is approaching $6 billion in gross profits. At some point it will run out of money to spend and will generate profits. I have a feeling that there are enormous profits that would flow out of Block right now if the company were more parsimonious in its spending. It is hard to understand how the company manages to spend half a billion dollars per quarter in R&D, for instance.

Perhaps Block would benefit from an activist investor. I am generally not a fan of activists because they tend to be short-term oriented. Alas, activism at Block is impossible. Insiders own 11 percent of Block’s economic interest but control over 48 percent of the votes.

In the company’s last annual meeting, a proposal was set forward to eliminate Block’s super voting stock.

The response from Dorsey and McKelvey was that “Our focus on long-term growth has created significant value for our stockholders since our initial public offering. We have achieved a gross profit CAGR of 53% over the past six years.”

This is true: despite the recent share price decline, since its IPO Block’s shares have returned 801.6 percent compared with 122.9 percent for the S&P 500 including dividends. Yet over the last three years, the S&P 500 index has returned 55 percent including dividends compared with only 17 percent for Block.

Sadly, the proposal at the AGM did not get approved.

There is enormous potential for profitability at Block, and for great capital allocation beyond that, such as dividends and stock buybacks. Ironically this would benefit every Block employee much more than the current path, since employees are richly rewarded in stock and shares of companies that pay dividends and buy back their shares tend to be less volatile (and certainly less volatile than Block’s, which has an incredible Beta of 2.11).

Block also has a simple path to get there: consolidate teams from the various recent acquisitions (Tidal, Credit Karma, AfterPay), sharpen the pencil on current operating expenses, and then make sure future operating expenses grow more slowly than gross profits.

One can only hope that Dorsey, McKelvey and Ahuja will one day shift their focus from “gross profit CAGR” to “free cash flow per share CAGR.”