Salesforce’s Best Acquisition Yet: Itself

Salesforce is the granddaddy of cloud stocks. It was the first sizeable SaaS company to go public, in 2004, and put the idea of software as a service on the map. Its origins trace back to the late 90s, after Marc Benioff had been at Oracle for ten years. He was afraid he’d become a lifer. So, he did what many of us wish we could do: he took a sabbatical and rented a hut to swim with dolphins in Hawaii, followed by a trip to India where he met “the hugging saint” Ammachi. She explained Benioff didn’t have to choose between giving back and pursuing his career: he could do both. This would become the origin of Salesforce’s giving pledge.

Around that time, customer relationship management (CRM) and sales force automation (SFA) company Siebel Systems went public. Benioff had worked with Tom Siebel at Oracle. In his book Behind the Cloud, Benioff recounts the genesis of Salesforce:

SFA is a huge market; every company has some kind of sales force. In the late 1990s, when I was investigating the category, there was certainly room for improvement. Enterprise software was especially burdensome for the customer.

[…]

I had a number of conversations with Tom Siebel about creating an online CRM product. Typical licensing software was selling for extraordinary amounts of money. The low-end product could start around $1,500 per user per license. Worse, buying pricey software wasn’t the only expense. There could be an additional $54,000 for support; $1,200,000 for customization and consulting; $385,000 for the basic hardware to run it; $100,000 for administrative personnel; and $30,000 in training. The total cost for 200 people to use a low-end product in the 1990s could exceed $1.8 million in the first year alone.

Most egregious was that the majority of this expensive (and even more expensively managed) software became “shelfware,” as 65 percent of Siebel licenses were never used, according to the research group Gartner.

I told Tom about the SaaS CRM solution I envisioned. We would have “subscribers” pay a small monthly fee ($50 to $100, which added up to less than half the cost of the traditional systems), and we’d “operate” it so there would be no messy installation for the customer. Tom liked the idea so much that he invited me to join Siebel.

But Siebel didn’t see the opportunity as big as Benioff, so Benioff decided to start the company on his own.

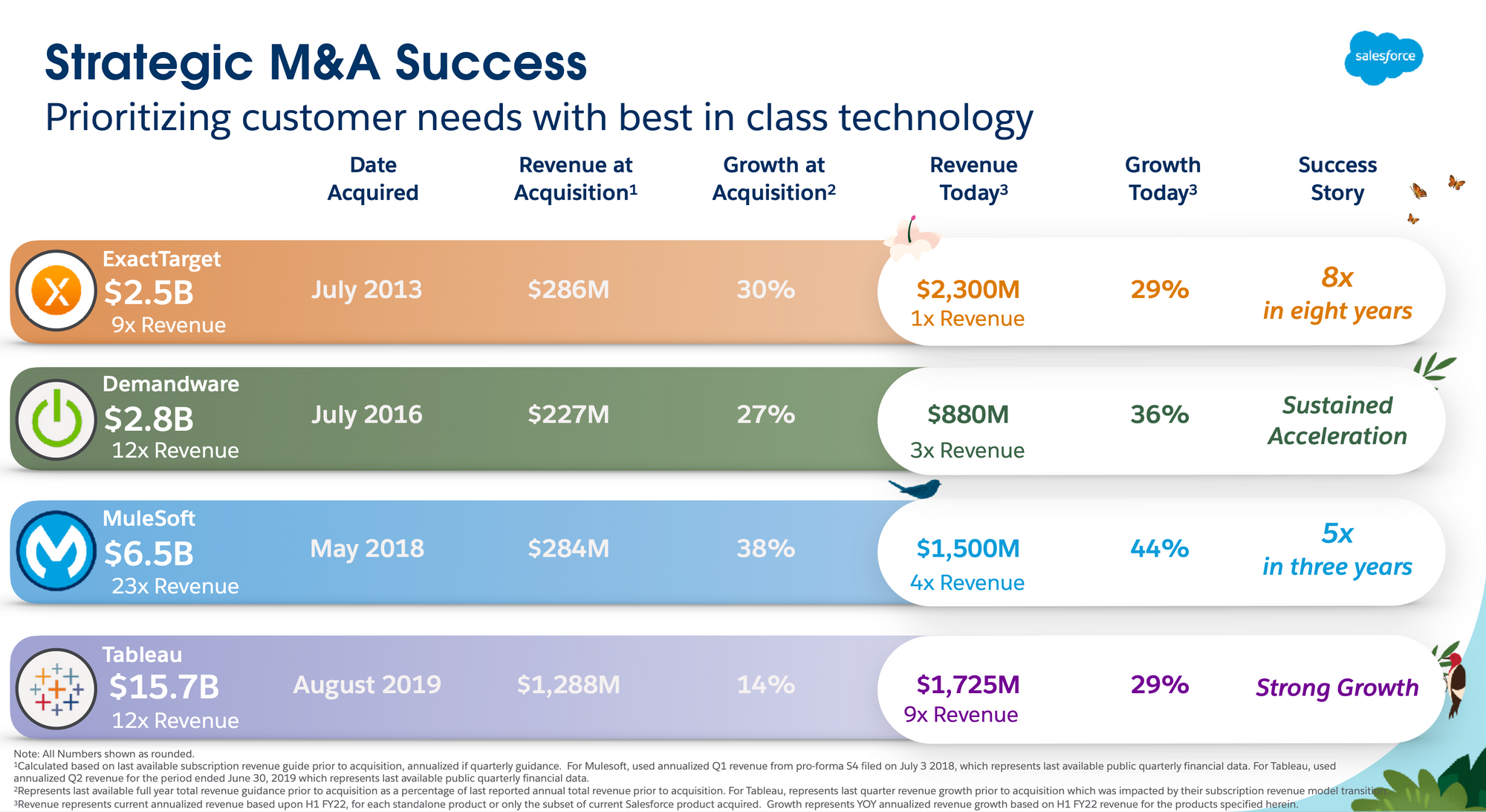

Following Salesforce’s successful 2004 IPO, the company has growth both organically and through acquisitions. While a full tally of the value of Salesforce’s acquisitions isn’t easy to put together, the company has spent over $50 billion buying other companies. The most sizeable of these have been in recent years, with the $27.7 billion acquisition of Slack in 2020, $15.7 billion for Tableau in 2019, and $6.5 billion for MuleSoft in 2018.

Several of these acquisitions were financed through the issuance of stock. Coupled with stock-based compensation, the number of Salesforce shares outstanding has grown at an annual compounded rate of 5.1 percent per year since 2004.

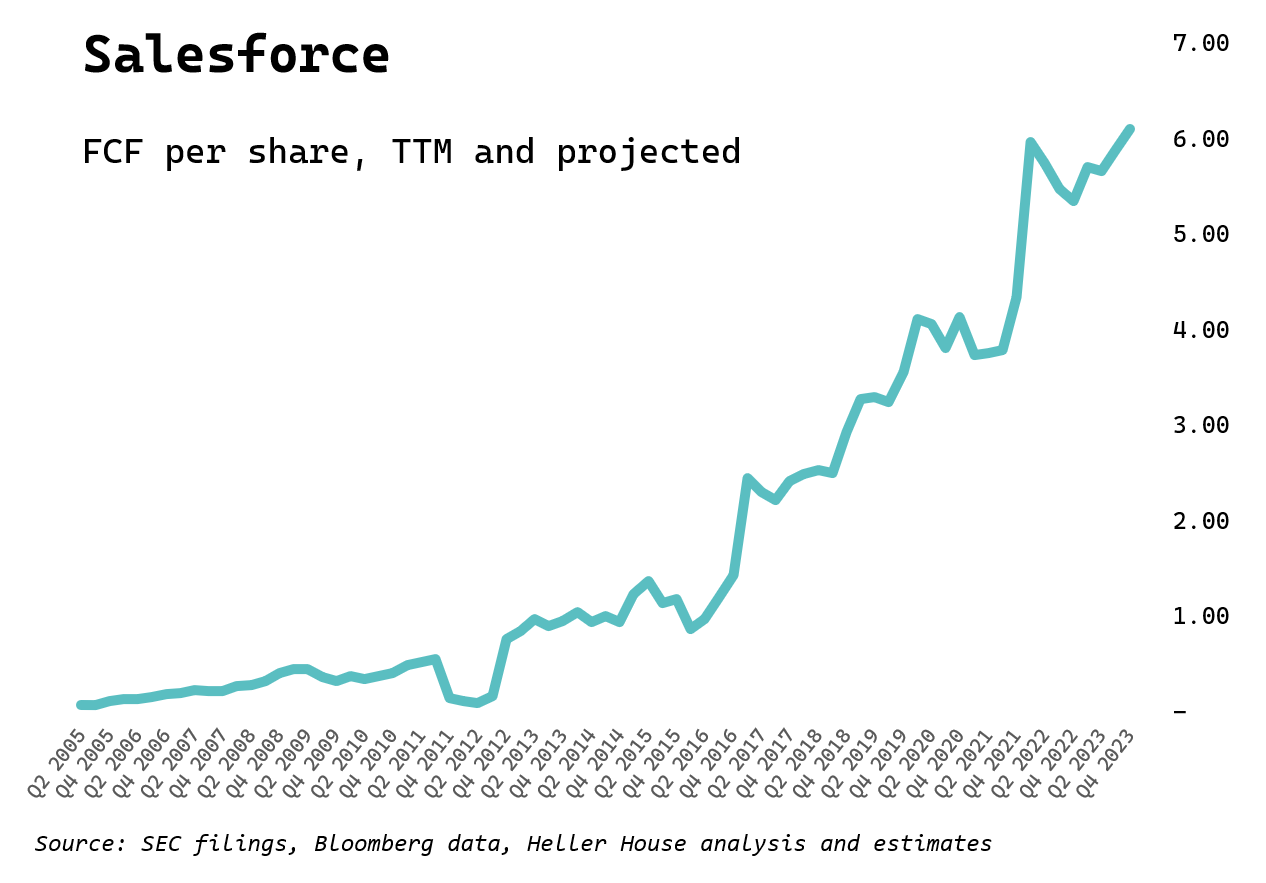

Despite this persistent dilution, Salesforce has delivered a rising stream of free cash flows per share, and as a result the stock had a total return of 6,234 percent to shareholders since the IPO compared to 430 percent for the S&P 500 index during the same period. During this period, stock-based compensation has been around 46 percent of reported free cash flow.

The chart below tracks this progress in free cash flow per share, showing estimated free cash flow through the end of fiscal 2023:

Notably, none of Salesforce’s numerous acquisitions—not even Slack, at $27.7 billion—generated any meaningful free cash flow at the time of the acquisition. Salesforce’s strategy has been to acquire subscription SaaS companies, integrate them into its world-class distribution, and begin generating free cash flow from the acquired assets after a few years.

The strategy has worked. As shown in the slide below, in nearly every case Salesforce has been able to accelerate growth, resulting in current revenue multiples substantially below those at the time of the acquisition:

Salesforce’s Best Acquisition: Itself

It’s a sign of a company’s maturity when it stops looking only externally for acquisitions and starts also looking at itself. It’s a sign that free cash flows have grown in dollar value substantially enough that a sensible investment becomes the company’s own shares. Each share represents ownership in all of Salesforce’s previous acquisitions. Since they’re performing so well, why not double down?

Companies have a limited number of capital allocation choices to make. They can use cash flow generated from operations to:

- Invest in their own business (generally through capital expenditures)

- Acquire other businesses

- Pay down debt

- Pay dividends

- Buy back their own stock

How the company chooses among this list depends on the return on capital that is available on each choice. Companies that can invest capital in their own business at high rates of return should do that rather than, say, pay dividends.

For example, I estimated that Tesla spent about $25 billion in cumulative capex to create its installed base of gigafactories, which have a capacity to produce 1.9 million vehicles. That’s a cost of about $13,000 per vehicle. Yet Tesla generates cash flow per vehicle of $12,700 per year, or free cash flow per vehicle of $6,300. These are huge returns on investment (depending on how one looks at it, a payback period of 1-2 years). Given Tesla’s ambition to keep building factories and scale 10x from this current installed base, and the very high returns it can earn on capital investments, it’s logical that Tesla should keep investing in its business rather than pay dividends.

SaaS companies like Salesforce typically measure LTV/CAC, or the lifetime value of the customer divided by the cost of customer acquisition. The higher the LTV/CAC, the more attractive it is to keep reinvesting in customer acquisition rather than any other capital allocation option.

At enough scale, however, there is simply enough cash flow left over to balance these alternatives. Large, successful companies can often walk and chew gum: they can reinvest in their businesses, make acquisitions, start buying back their own stock, and perhaps even pay dividends.

The inflection point into this new capital allocation phase can be particularly lucrative for investors, given the initial conditions are favorable.

Apple is the poster child for such an inflection point. The company began its stock buyback program in late 2012. Since then, it has repurchased a cumulative $529 billion of stock, while paying a cumulative $128 billion in dividends.

Its share count has done the mirror opposite of Salesforce’s, shrinking by a compounded annual rate of 5 percent per year.

The result is a stock that generated a total return of 916 percent compared with 247 percent for the S&P 500 index since the last day of 2012.

This is a 27 percent annualized return for Apple compared with 13.8 percent for the index. This return was not the result of extraordinary revenue growth: over the period, Apple’s revenues grew just 9.4 percent compounded.

Initial conditions were very good: Apple’s P/E ratio was about 11x. It has re-rated massively, to 27x currently.

But look at what the buyback did: Apple’s free cash flow grew only 5.7 percent compounded during the period (since Q1 2013), but because of buybacks, free cash flow per share grew 11.3 percent compounded.

GAAP net income compounded close to revenue, at 9.6 percent per year, but net income per share compounded at 15.4 percent, again reflecting the benefit of share buybacks.

Apple has not compromised its balance sheet while pursuing these capital allocation goals: the company still has a net cash balance of $60 billion and generated a massive $135 billion of EBITDA over the last twelve months. Nor has it skimped on investing in its business, with its $5 billion Apple Park and numerous successful product introductions since then.

Salesforce has now crossed this Rubicon. In its Q2 2023 earnings call held last week, Benioff nodded to Salesforce’s acquisitive past and announced Salesforce’s next M&A target:

We always get questions about our M&A strategy and what company we're going to acquire next and what we're going to do next from an acquisition cycle. I think we get this question every single earnings call that we do like this. And it's always one of my favorite parts of the call.

And I'm excited to tell you we have found a great cloud company, growing revenue for 73 consecutive quarters through every economic cycle. It's got great cash flow, #1 market share, an incredible brand, one of the most admired companies in the world, great values, fantastic community of 17 million Trailblazers, fantastic commitment to its community, runs across 90 countries.

And that company is Salesforce.

We're thrilled that our Board of Directors has authorized up to $10 billion in our first-ever share repurchase. This reflects the confidence we have in our business and in our approach to generating shareholder value.

Later in the call, co-CEO Bret Taylor added:

Our capital allocation strategy is simple. We will continue to expand our free cash flow margin as we scale. We will invest in our organic innovation. We will reduce the impact of dilution, both by offsetting stock-based compensation and by maintaining a healthy balance sheet to fund any future M&A.

Salesforce as an Investment

Taylor hit all the key points in his concise statement. At Salesforce’s scale—the company is on track to generate $6.2 billion of free cash flow this year—it doesn’t have to choose one capital allocation option or another. Like Apple, it can have a balanced approach.

Salesforce’s Board of Directors—which is chaired and vice-chaired by Benioff and Taylor—approved a $10 billion buyback which is hopefully just the starting point for Salesforce.

The company has a strong balance sheet with no net debt and, given the long runway ahead for Salesforce’s products, many years of growth.

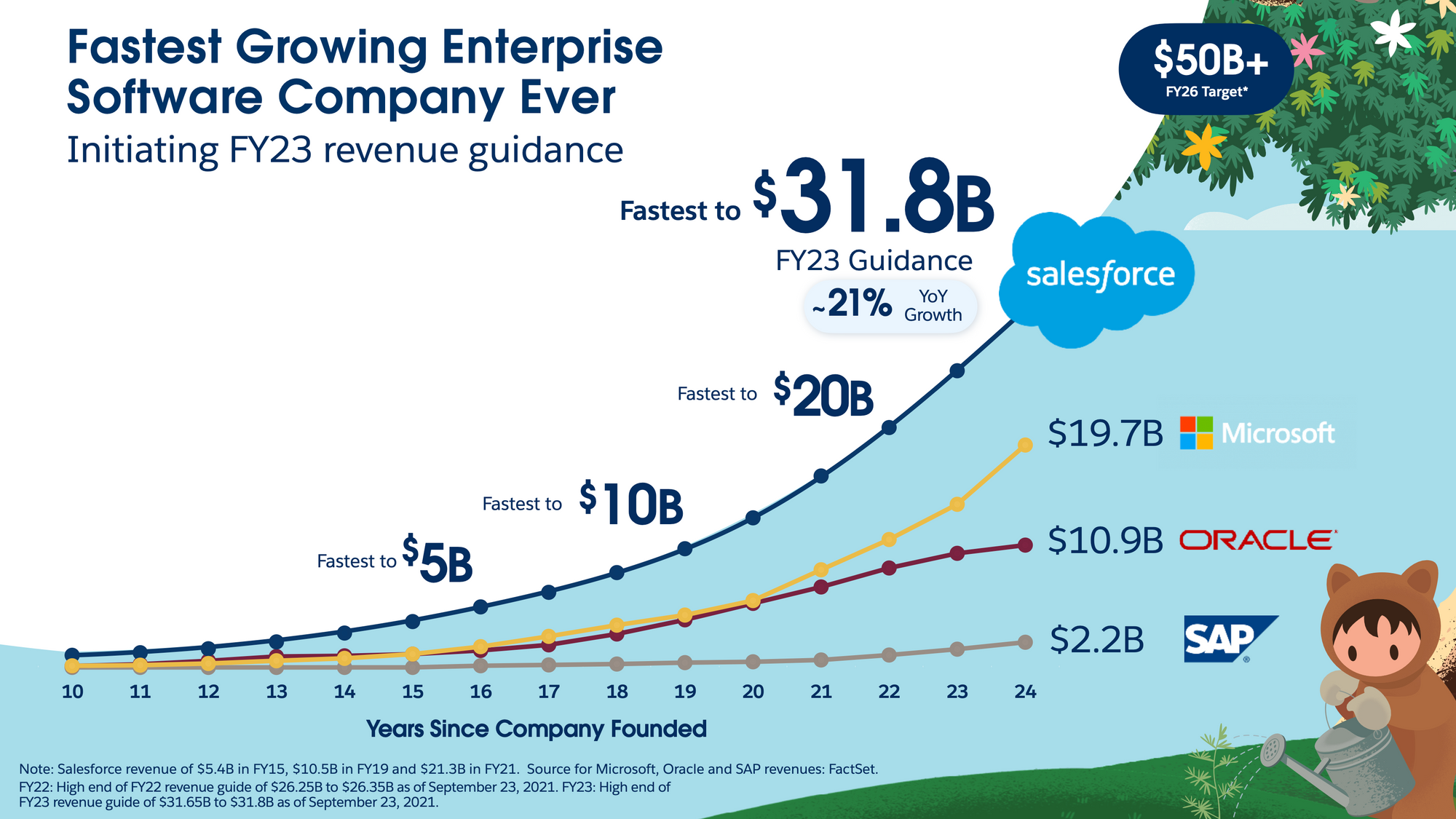

In fact, in the call the company reiterated its $50 billion revenue target for fiscal 2026. Sell side analysts we on board with this goal, estimating $52 billion of revenue by then as recently as March of this year. With Salesforce’s guide-down—the company flagged FX headwinds and a “more measured” demand environment—analysts are projecting just $48 billion of revenue by 2026.

Either way, Salesforce remains among the fastest-growing enterprise software companies in history, as it likes to remind investors during its yearly investor events:

Let’s give Salesforce the benefit of the doubt: that the company will achieve its $50 billion revenue target by fiscal 2026, deliver rising free cash flow margins as promised by Taylor, and continued growth thereafter.

Given its current free cash flow yield of 3.8 percent—about $6.1 in free cash flow per share divided by its $162 stock price—and the historical multiple range at which the company has traded, Salesforce could afford to buy back about 3.3 percent of the company’s shares every year.

This would offset dilution to a certain extent and, assuming Salesforce can reduce yearly dilution to around 2 percent per year, begin actually shrinking the company’s share count.

It would do wonders for free cash flow per share. By deploying all its free cash flows to buybacks, Salesforce could grow free cash flow per share in the high teens for at least the next five years.

Without buybacks, free cash flow per share would grow merely at mid-teens. Over time, these seemingly small differences compound enormously.

As the Apple example demonstrates, buybacks can improve long-term returns dramatically. If Benioff visited Ammachi again today, she would probably tell him he can do both: pursue external M&A and buy back his own stock.

Salesforce can make history again, becoming the first large SaaS company to IPO and, nearly two decades later, the first to aggressively shrink its share count. If that’s the case, shareholders will applaud this stalwart’s newfound religion.