How Mismanaged is Block?

I used to think that Block, the payments and digital banking company previously known as Square, was well-managed. It’s a consistent grower, and every cohort of user it acquires is profitable on a gross profit basis. These cohorts have a short payback period of around a year (lately, this payback has extended a bit, but it’s still a business with a high return on invested capital). Furthermore, Block acquires users for a fraction of what traditional banks pay for their users.

So far, so good.

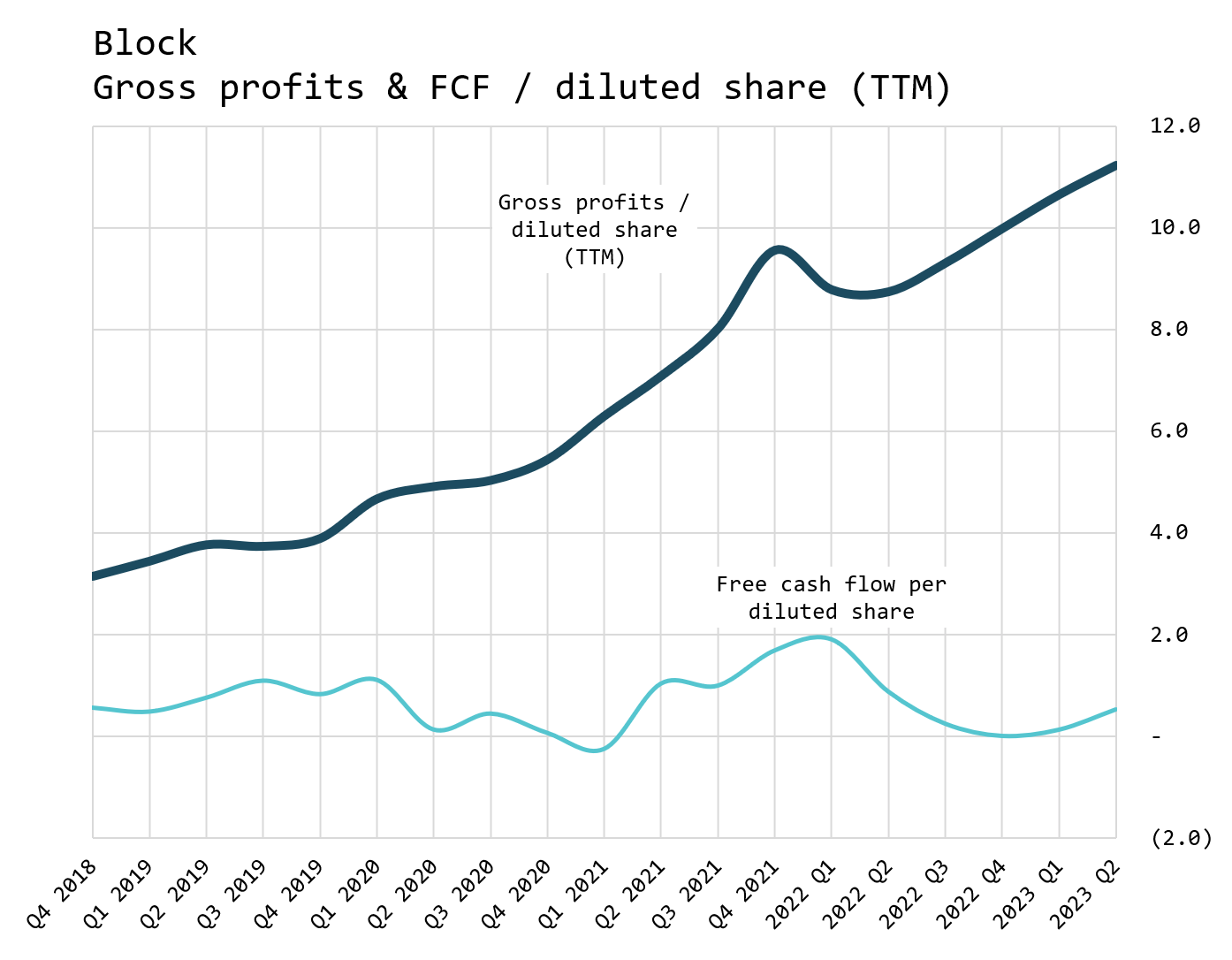

Block has been unable, however, to translate its steadily growing stream of gross profits—how much cash it brings in from revenues, less the cost of generating those revenues—into any meaningful operating profits or free cash flows.

That stream of gross profits has ballooned and is expected to reach $7.4 billion this year, up from $6 billion in 2022. This is significant scale. Block should be printing free cash flows. But it’s not.

What’s eating up all those gross profits?

A never-ending rising stream of expenses. Over the last twelve months, Block has poured $2.5 billion into product development. This is an astonishing number for what is effectively a software business (yes, Block sells hardware terminals as a customer acquisition tool, but these are not changing radically every year and don’t require massive R&D investment).

For comparison, a company with a similar level of gross profits, Airbnb, spent about $1 billion in R&D in the last year.

Next is sales and marketing, at $2.1 billion. This expense is more defensible, given that the company continues to grow briskly, yet management has admitted recently that a lot of this spend is “experimental” and can be further optimized.

Finally, there is $1.8 billion of general and administrative expenses, which also feels like it should be a lot less.

Why does it feel that way?

Because companies generating this much in gross profits are generally profitable. Not “just” profitable, but massively so.

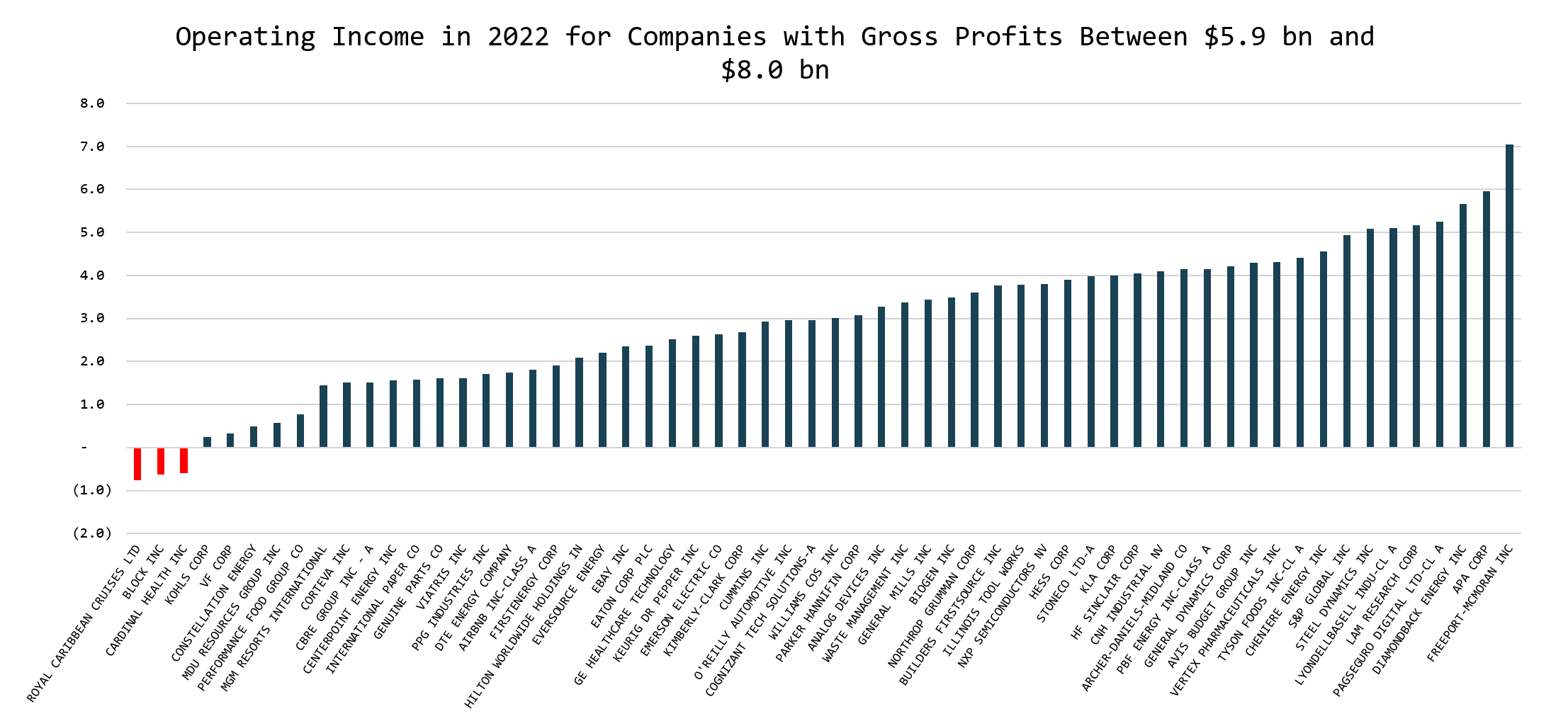

To prove this, I ran a screen for companies with gross profits between $5.9 billion and $8.0 billion in 2022. The wide range was chosen to include Block as it was in 2022, as well as where it’s headed in 2023 and beyond.

In the chart below, I show the results. The 60 companies are sorted by operating profit generated in 2022:

Block is second from dead last, next to Royal Caribbean, a company that has fantastic cruises but is not in an industry known for generating attractive returns on invested capital.

The companies on the list are quite diverse, but companies that are similar to Block can be spotted.

Airbnb did $6.9 billion in gross profits and $1.8 billion in operating income. Ebay had $7.1 billion in gross profits and $2.4 billion in operating income.

South American payments companies StoneCo and PagSeguro did $6.9 billion and $7.9 billion in gross profits and $4 billion and $5.2 billion in operating income, respectively.

None of these companies are perfect comparables to Block, of course, but I think this shows how bloated Block is. This year Block is aiming at operating income of—get ready for it—$25 million. This feels at least $1.5 billion too low. The median company in this chart is generating $3 billion in operating income. No wonder Block's stock sold off 28 percent this month following the earnings release.

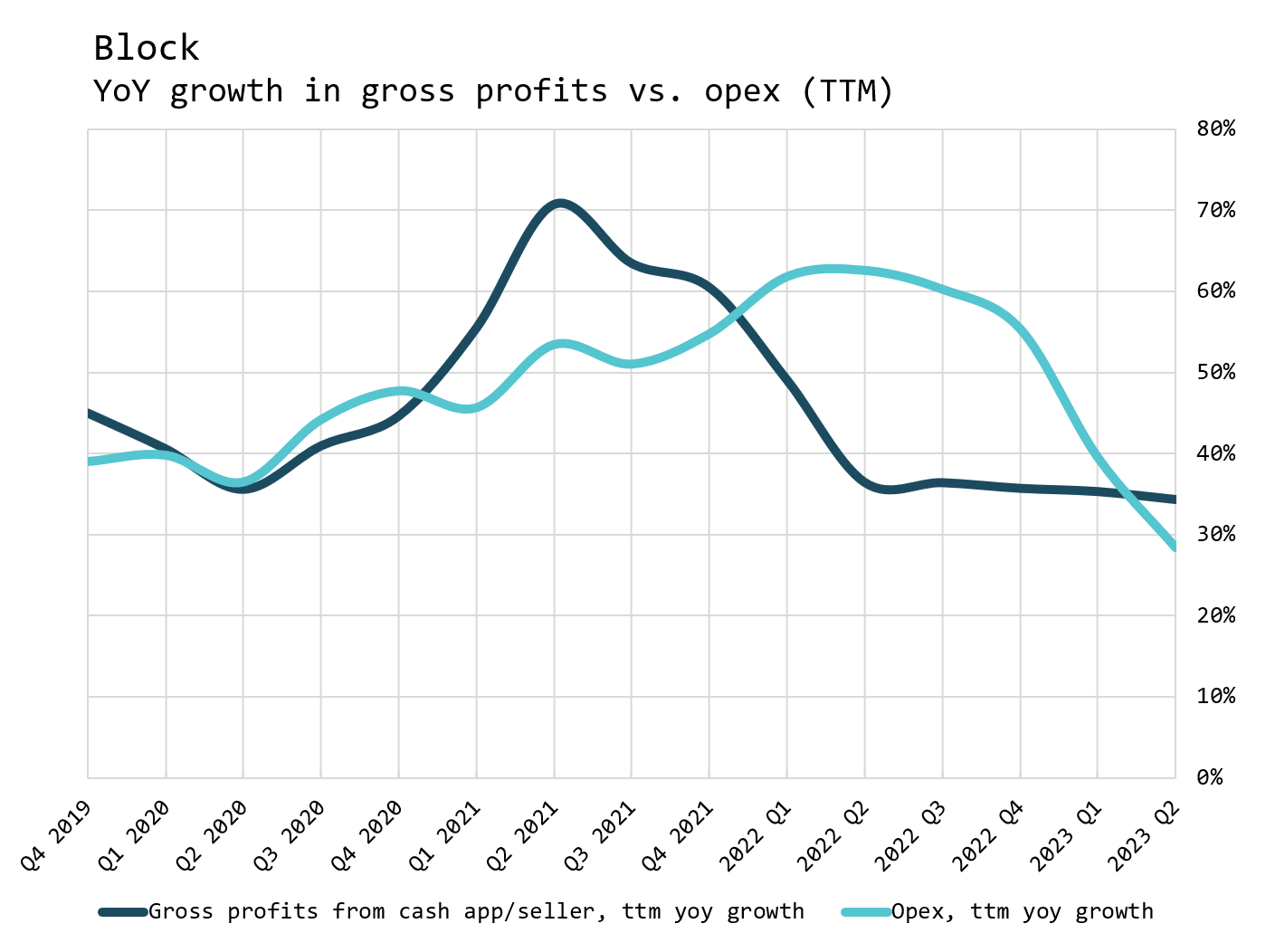

So far, we are ignoring growth. Yes, Block is growing briskly, and grew gross profits 36 percent year-over-year from 2021 to 2022.

But the similar companies also grew. Airbnb grew gross profits 43 percent in the same period; StoneCo grew 122 percent; PagSeguro grew 68 percent; eBay was the laggard with an 8 percent decline.

What other clues do we have to reach the conclusion that Block is mismanaged?

We can look at Twitter after it was acquired by Elon Musk.

Musk noted that the catered lunches alone were costing the company over $400 per lunch served. He was able to then lay off around 80 percent of the staff. Since then, the velocity of features and product improvements has increased dramatically. Nobody seems to know what those thousands of Twitter employees did; they certainly didn’t contribute to the business.

(Note: some argue that Twitter’s ad revenue declined post acquisition as a result of that staff having been laid off. This isn’t true: the reality is that advertisers pulled back because the mainstream media published a lot of stories about unsafe speech on Twitter. Ad revenues are now improving at X, the company’s new name.)

Twitter’s CEO was Jack Dorsey from 2015 through late 2021. Dorsey is currently the CEO of Block. It is not a stretch to reason that if Twitter was so loose with its operating expenses, so is Block.

Indeed, Dorsey admitted as much in Block’s Q2 earnings call:

As we shared earlier this year, we define our investment framework as Block and each ecosystem must show a believable path to gross profit retention of over 100% and Rule of 40 on adjusted operating income.

Today, I wanted to share our progress towards this target and demonstrate how our investment framework forces us to make trade-offs and guides our decision-making across the company.

Leaders across our company are now looking at the true full cost of their businesses, inclusive of share-based compensation. This has led us to pull back on our pace of hiring to be more targeted in hiring for critical roles and to focus more on performance management.

A very basic rule of management is that a business unit leader must understand his or her own profit and loss statement, as well as how much capital is being tied up in that business unit.

A business unit that generates $100 million of operating profit might sound attractive; but if that business unit requires $1 billion of capital (in the form of servers, for instance), that’s not very attractive at all: a 10 percent return on capital doesn’t create value for a publicly traded company whose shareholders expect a much greater return on capital.

In this context, this admission by Dorsey is nothing short of shocking. “Leaders across our company are now looking at the true full cost of their businesses, inclusive of share-based compensation.”

This means that previously, leaders were unaware of the full cost of their businesses; they didn’t even know their own profit and loss. How can a company be run this way?

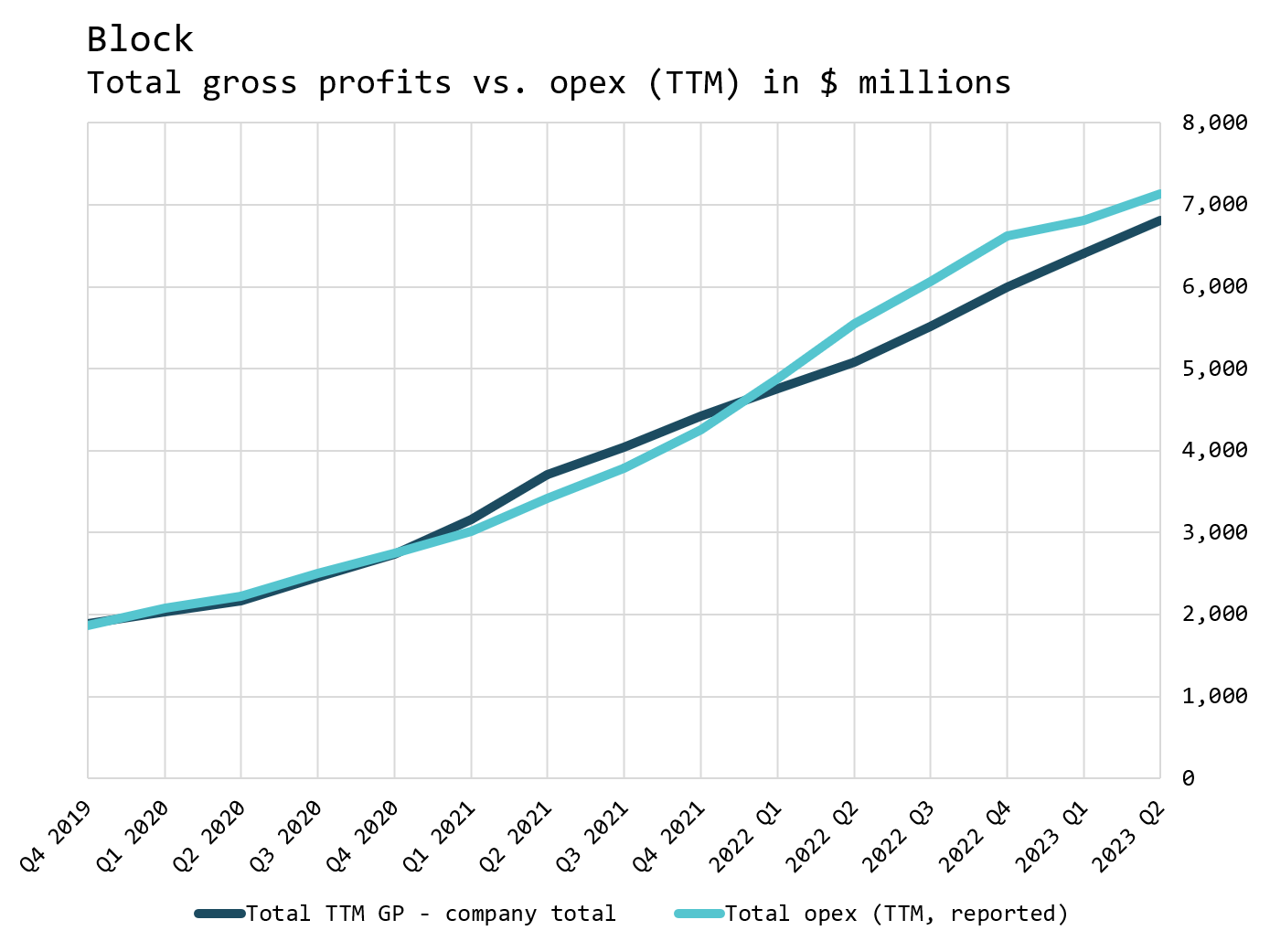

The answer is that it can’t. And it shows. Block keeps pouring money into operating expenses without regard to profitability. As goes the gross profit line, so goes operating expenses:

Block shareholders have been imploring Jack and Amrita to control operating expenses for several quarters now (I know this, because I am a Block shareholder, and I have been writing them detailed emails about these topics for a while. I bet I’m not the only one).

Only this last quarter did the company finally pull back, with operating expenses growing less than gross profits. While the company keeps talking about adding more headcount, I suspect that if properly managed, it could do quite a bit more with dramatically less headcount.

Recently, Block laid out a new profitability framework: its goal is to reach a Rule of 40, including stock-based compensation. For example, if gross profits are growing at 20 percent, operating income (including SBC) must be 20 percent of gross profits.

When this framework was announced in Block’s Q4 2022 earnings call, Dorsey made it sound like an ambitious goal:

There are three principles guiding our investment framework. Number one, ensure our investments are focused on customer retention and growth. Number two, account for ongoing costs of the business including stock based compensation. And number three, utilize industry standard conventions that are simple to communicate and to understand. Using these principles, our investment framework can be articulated in a single sentence. Block in each of our ecosystems must show a believable path to gross profit retention of over 100% and Rule of 40 on adjusted operating income. This is an ambitious goal, especially at our scale and one we aren't meeting today.

But if we inspect the same cohort of 60 companies above, it turns out that their median “Rule of 40” (as defined by Block) is a whopping 60 percent.

To measure this, I took fiscal 2022 gross profits for each company and compared the growth over fiscal 2021; then I added this to the fiscal 2022 operating profit divided by 2022 gross profits (to arrive at Block’s adjusted operating margin).

Once again, Block is ranked near the bottom, fourth from the left on the list:

Certainly, some of these companies are cyclical and saw a wild swing in gross profits. But the Rule of 40 for our similar companies is quite comparable. Airbnb’s was 69 percent, PagSeguro 135 percent, StoneCo 180 percent, and eBay was the laggard, matching Block’s 25 percent.

Based on this analysis, it’s more than clear to me that Block is dramatically underachieving at its current scale. This company should be a lot more profitable than it is, even accounting for growth.

What can management do? Aggressively implement a zero-based budgeting program, scrutinizing every cost line item with a beginner’s mindset. It can also start demanding a lot more from its existing team and implement a reduction in force of at least 20 percent (assuming this trims operating expenses by 20 percent, the company would immediately generate $1.5 billion in operating income). Stock-based compensation should be tied to achievement of the Rule of 40 goal, and should be restructured to minimize dilution.

What does this mean for Block’s stock?

Below are two scenarios. The left one is, frankly, table stakes. I call it the “bare minimum” scenario. Growth decelerates, but operating expense growth is much more conservative. Stock dilution is kept at 4 percent per year. Mechanically, this will raise margins to a respectable 29 percent by 2027.

I’m using a generous 25x earnings multiple here. I don’t know if a slower-growing Block would merit that, but my intuition is that it would, because it would be massively profitable and investors would finally be able to look at GAAP earnings and returns on invested capital.

The scenario on the right is a bit more optimistic, with more aggressive cost control and lower stock dilution, while keeping growth the same as on the left-hand scenario. One can certainly quibble with these assumptions, but the point is that directionally the company must get serious about its costs.

The returns from the current share price of around $58 are not bad. But the only way the stock works from here, in my view, is if Jack and Amrita become aggressive about running this as a profitable business and not just a vanity project.